"We Saw The Water Turning Red"

In 1916 a Shark Arrived at the Jersey Shore and Wouldn't Go Away

Amidst the sun-drenched days of a bustling holiday season, a picturesque coastal town becomes a haven for swimmers and beachgoers. Families, couples, and friends flock to the water, eager to soak up the warmth and revel in the refreshing embrace of the ocean waves. The shore is alive with laughter, the scent of tanning oil, and the carefree spirit of summer.

It was a serene summer evening in Beach Haven, New Jersey. The sun dipped below the horizon, casting a golden glow over the Atlantic Ocean. He waded into the cool, inviting waters. The rhythmic sound of the waves and the distant laughter of beachgoers filled the air. As he swam, he felt something brush past his leg. At first, he dismissed it as driftwood or seaweed. But soon, he felt it again—something too big and too alive, something that felt like sandpaper. An eerie sense of dread washed over him, but before he could react, the water around him exploded in a frenzy of thrashing and roiling red water...

It is not incidental if you're now picturing Amity Island and Brody, Hooper, and Quint's Melvillesque battle with a 25-foot Great White. It's by design. The idea of a shark preying on the population of a small Northeastern area without warning does not originate with the film "Jaws" or the novel it was based on. In fact, the book "Jaws" owes its existence to something that occurred much earlier, in the winding path of the Long Island River, at a time when the nation was still free of the horrors of "The Great War" unfolding on the other side of the Atlantic.

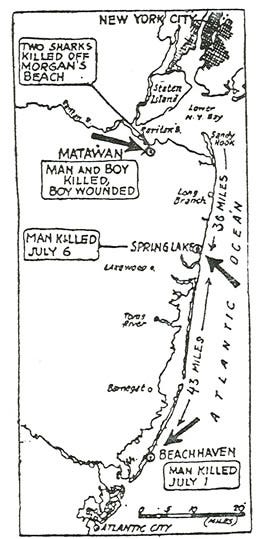

Visitors to the Jersey Shore that summer encountered a different kind of horror. A series of unprecedented and violent shark attacks occurred between July 1 and July 12, resulting in the deaths of four people and severe injuries to another. This event marked a significant turning point in public perception of sharks and sparked a wave of fear and fascination that endures to this day.

The first attack occurred on the evening of July 1. Charles Vansant, a 25-year-old from Philadelphia, was vacationing with his family at the Engleside Hotel in Beach Haven. That evening, Vansant decided to take a swim before dinner. He ventured into the Atlantic Ocean accompanied by a dog. A shark suddenly attacked him as he swam, gripping his left thigh, tearing chunks of flesh away, and turning the water crimson.

Eyewitnesses on the beach, including lifeguard Alexander Ott and bystander Sheridan Taylor, heard Vansant's cries for help. They rushed into the water, pulling him from the shark's jaws and dragging him to shore. Vansant's father, Dr. Eugene Vansant, attempted to stop the bleeding, but the severity of the injuries was overwhelming. Vansant was carried back to the hotel, where he bled to death on the manager's desk. The attending physician noted that Vansant's leg had been severely lacerated and stripped of flesh, injuries characteristic of a shark attack.

Ott recounted, "He was screaming and thrashing, trying to free himself. When we pulled him out, there was so much blood; it was horrifying. I had never seen anything like it."

Five days later, Charles Bruder, a 27-year-old Swiss bell captain at the Essex & Sussex Hotel, decided to swim during his lunch break. Around 130 yards from the shore, Bruder was attacked by a shark. His screams for help alerted several hotel guests and lifeguards, Chris Anderson and George White, who rowed out to rescue him.

Hotel guest Gertrude Schuyler described the scene, saying, "I heard the most terrifying screams and saw a man thrashing in the water. The lifeguards brought him back, and his legs were gone. It was a scene of absolute horror."

Upon reaching Bruder, they found him floating in a pool of blood, with both legs severely bitten off. The lifeguards managed to get him onto their boat, but Bruder bled to death before they reached the shore. His body was carried to the hotel, where horrified guests and staff gathered, witnessing the gruesome aftermath of the attack.

The next attacks occurred inland, in Matawan Creek, a narrow tidal river connected to Raritan Bay, about 30 miles north of Spring Lake. Lester Stillwell, an 11-year-old boy, was swimming with friends in Matawan Creek, a narrow tidal river near Keyport. Around 2:00 PM, while playing in the water, Lester was suddenly pulled under by a shark. His friends ran to town for help, screaming that a shark had taken their friend.

Lester's friend, Albert O'Hara, said, "We were all splashing and playing, and then Lester just disappeared. There was blood everywhere, and we ran for help. It was the most terrifying thing I've ever seen."

Several local men, including 24-year-old Watson Stanley Fisher, hurried to the creek to search for Lester. Fisher dove into the creek, and as he searched, the shark attacked him, inflicting severe wounds to his right thigh. Despite being rescued and brought to shore, Fisher died later that evening in a local hospital from blood loss.

Later that same day, just a half mile downstream, Joseph Dunn, a 14-year-old boy from New York City, was swimming in Matawan Creek. Joseph was unaware of the earlier incidents despite the publicity and growing hysteria. Around 30 minutes after Fisher was attacked, the shark struck again, biting Joseph's leg.

Joseph's brother, Michael Dunn, said, "We saw the water turning red and realized Joey was in trouble. We pulled him out as fast as we could. The shark didn't want to let go. It was a miracle he survived."

Michael and several friends managed to pull Joseph from the water, fighting off the shark. They rushed him to St. Peter's Hospital in New Brunswick, where he was treated for his injuries. Unlike the other victims, Joseph survived, though he suffered severe damage to his leg.

The early 20th century was a time of significant social and environmental change in the United States. Urbanization, industrialization, and an increasing middle class with leisure time led to a rise in seaside tourism. People flocked to the beaches to escape the summer heat, and swimming became a popular pastime. However, the understanding of marine life, particularly sharks, was limited. Sharks were not widely perceived as a threat, and the general public was largely unaware of their behavior and habitats.

The New Jersey coast was considered safe with its bustling resorts and tourist-friendly beaches. The concept of a shark attack seemed more like a plot from a sensational story than a real-life danger. The sudden spate of attacks challenged this perception and caused widespread panic. Newspapers, already competing for readers with lurid stories, seized on the shark attacks, amplifying the fear and fascination surrounding these incidents.

The 1916 shark attacks had an immediate and lasting impact on both public consciousness and scientific inquiry. The fear generated by these events led to a temporary decline in seaside tourism and prompted authorities to take drastic measures. Local governments in New Jersey and other coastal states implemented shark hunts, deploying nets, patrols, and even dynamite to eradicate the perceived threat. Although these measures did little to actually reduce shark populations, they reflected the extent of public anxiety.

Scientifically, the attacks spurred interest in shark behavior and biology. Experts began to study sharks more closely, seeking to understand their feeding habits, migration patterns, and interactions with humans. This period marked the beginning of a more systematic approach to marine biology and the study of sharks, leading to greater knowledge and, eventually, to more effective conservation efforts.

Culturally, the attacks influenced popular media and literature. They inspired several stories, books, and films, most notably Peter Benchley's 1974 novel "Jaws" and its 1975 film adaptation directed by Steven Spielberg. "Jaws" amplified the fear of sharks to a new level, portraying them as cunning, malevolent creatures. While thrilling for audiences, this portrayal contributed to widespread misconceptions about sharks and justified the continued demonization and hunting of these animals.

The environmental conditions in the summer of 1916 may have played a significant role in the shark attacks. Some theories suggest that unusually warm weather, ocean temperatures, and increased coastal activity due to the summer season could have attracted sharks closer to shore. Additionally, World War I was ongoing, and submarine warfare might have disrupted normal shark behavior, driving them to new hunting grounds.

Another factor to consider is the type of shark involved. The species responsible for the attacks was never conclusively identified, though theories have included the great white and bull sharks. Bull sharks are particularly noted for their ability to swim in both salt and freshwater, which could explain the attacks in Matawan Creek. The lack of definitive identification has left room for continued speculation and study.

In the years following the 1916 attacks, our understanding of sharks has evolved significantly. Research has shown that shark attacks on humans are extremely rare, and most species pose little threat to people. Sharks are now recognized as essential components of marine ecosystems, playing a crucial role in maintaining the balance of oceanic life.

Conservation efforts have gained momentum as the importance of sharks to biodiversity and the health of the oceans has become apparent. Many species are now protected, and public education campaigns aim to dispel myths and promote coexistence with these ancient predators.

The legacy of the 1916 shark attacks remains a stark reminder of the delicate relationship between humans and the natural world. It highlights the impact of fear and misunderstanding and the potential for growth in knowledge and respect for marine life. As we continue to explore and interact with the oceans, the lessons from that fateful summer remind us to approach nature cautiously and curiously.

I am sure, however, that you are thinking what I’m thinking: no matter what the experts tell you, never assume it's safe to go back in the water. There are too many sharp teeth in too many unseen places.